To top off a marvelous weekend with cousins at the 80th birthday party for my Aunt Helen in Springfield, Massachusetts, we veered off the main highway and drove up Route 7 on our way home to check out Mass MOCA.

Fortune smiled on my art loving self, because that route also led by The Clark Museum in Williamstown, so we drove in to check out the “Picasso Looks at Degas” exhibit, where works by the two artists were displayed side by side and emphasized the extent to which Picasso studied, responded to and was influenced by the elder artist’s work.

Entrance to The Clark. We arrived at 10 AM when the doors opened and by the time we left an hour later, the parking lots all around the building were completely full.

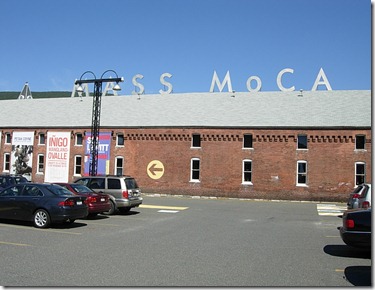

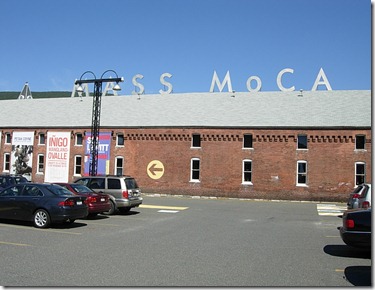

From there we drove on to North Adams and Mass MOCA, an amazing complex of factory buildings that opened in 1999. The buildings were restored and refurbished to house large scale installation works by contemporary artists.

Currently on exhibit there is a retrospective of Sol Lewitt’s work and “Material World”, an invitational in which seven artists were invited to transform the second and third floor galleries with installation pieces. All the artists selected are known for their use of modest, everyday materials. Each has produced a massively scaled work that responds to and interacts with the industrial environment of the space.

White Stag, 2009-2010. Paper, wood by artists Wade Kavanaugh and Stephen B. Nguyen. Twisted, crumpled and draped rolls of paper created this old growth forest, an enormous installation that spanned two floors.

Big Boss, 2009-2010. Rope, paint, by Orly Genger. The exhibit brochure reveals that the artist knotted (in an adapted crochet stitch) and painted over 100 miles of rope. Responding to the male-dominated world of sculpture, Genger’s work pumps up this traditionally female-identified craft process to the level of Olympic physical prowess. It is forceful and --surprisingly -- simple and familiar at the same time.

It becomes evident in viewing all the works that just how intensely physical the act of making them must have been.

The Sol Lewitt retrospective, which I expected to just appreciate as a viewer, turned out to be inspiring and informative to me as an artist, both in the sheer volume of the artist’s productivity and diversity of explorations and the philosophy and thought that led to his separation between artistic ideas and their execution.

LeWitt numbered his “wall drawings” rather than naming them. He engineered specific directions for each work’s creation, which are executed by artists and students at specific sites. The process is labor intensive and exacting and ephemeral. Often the walls are painted over and the paintings disappear when an exhibition closes. Mass MOCA is displaying this retrospective installation of 105 of the artist’s work for 25 years.

My personal favorites are the graphite pieces that LeWitt created both in his earliest works and then returned to at the end of his life. The final works appear luminous; they are comprised of carefully measured bands and densities of hand-scribbled lines using just graphite pencil lead.

The exhibit brochure copy describes these works as “transcendent.” I can’t help but agree.